Our First 50 Years

EARLY YEARS

Founded in 1972, the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies’ (wiiw) main tasks until 1989 were to act as a platform of exchange for economists from East and West of the Iron Curtain, and to analyse and understand the performance of the planned economies of Eastern Europe.

TODAY

Today, the institute is an internationally recognised applied-research institute focusing on the economic aspects of European integration, EU policies and EU enlargement, with a special interest in Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe (CESEE).

PERSPECTIVES

In the future, wiiw aims to place greater emphasis on key areas, such as climate change, digitalisation and the transformation of Europe’s economy towards increased competitiveness and sustainability, with the goal of shaping European and global policy.

Testimonials

Chief Economist, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)

Federal Chancellor of Austria 2000–2007, Founder of European Voices magazine

The

Tragedy

of Central Europe

1. Central Europe is a fiction – a beautiful fiction that consists of a peculiar intersection of misunderstood real history and misused utopia.

Yet the concept of Central Europe now hovers so high above reality that no contradiction can harm it. Politicians who like to use the term or the fantasy of Central Europe, at least in Sunday speeches, defend the opposite in their daily political practice, namely the political sovereignty and cultural specificity of their respective small nation-states, while writers and intellectuals use the term Central Europe to conjure up a cultural space that has long since been destroyed by nationalists, even before it could prove sustainable in reality. Nevertheless, with regret I must add that the concept of Central Europe does not cease to float, and to flash and cast shadows again and again from a lofty height, this only meaning that it has no grounding.

We would like history to have a goal, to be logical, and we find it difficult to acknowledge that history has all sorts of things in store for us, except this: reason and logic.

Fantastic Central Europe defined as a cultural space: it briefly showed itself to be real in its possibilities but was quickly rendered impossible. Only in this dichotomy was it ever real and can remain truly fantastic.

2. The misunderstood real history is the history of a misunderstood concept of freedom, which derived from the idea that freedom presupposes the sovereignty of a “nation” or an ethnic group on an ancestral territory. This idea was already reactionary in Central and Eastern Europe when it was historically young, when nationalist movements promised a new world of self-determination and powerfully shaped the era. For the Central European reality, at least within the broad area of the Habsburg Empire, had long since moved on and must, in retrospect, be described as world-historical avant-garde. There was for all “nations” (which at that time was a synonym for ethnic, linguistic, religious and somehow culturally definable groups) a common state of law, a common market, a common currency, a common administration or bureaucracy, a common foreign policy, and a common security policy in which all “nations” found their protection and provided regiments that satisfied the feelings of identity of the respective “nations” in the folkloric features of their uniforms. There was already everything that had to be painstakingly rebuilt over decades after the catastrophe of the second Thirty Years’ War (1914 – 1945) and then after 1989, after the liberation of the Soviet glacis states, and there was even more, because the European Union has still not been able to come to terms with a common security and defence policy. And in the constitution of the Habsburg Empire there was the guarantee of personal autonomy instead of the territorial autonomy demanded by the nationalists. This meant that as an individual one was a citizen and part of a group however defined (ethnically, linguistically, religiously, culturally), without this being linked to a specific territory or even to a claim to a specific territory. This old Austrian legal statute is still avant-garde today, considering that in the European Union one can only have European citizenship on the basis of the national passport of an EU member state.

3. The personal autonomy of the Habsburg Empire was the real political prerequisite for the development of what is nostalgically called “cultural space”, namely a spirit based on the coexistence of different language groups and their cultures, their exchange and, in part, their fusion, which permeated people’s everyday lives just as much as it expressed itself in fostering the most significant cultural achievements of the time.

The nationalists blew up this reality alongside its cultural, artistic, and scientific richness, including the binding legal status of personal autonomy. And if someone asked why a teacher, a coachman, a taxi driver, a peasant, or a factory worker should, on the basis of his/her nationality, have more in common, for example, with the wife of a factory owner of the same nation than with teachers or taxi drivers etc. of other nations, they were never able to get an answer from the nationalists.

So, the nationalists formed their little nations, and were thereupon helpless and defenceless against the storms of world politics: War, occupation, ethnic cleansing, genocide, dictatorships, and misery, this was the fate of the Central and Eastern European nations. Arbitrariness and lawlessness reigned after 1917 on their respective territories, which they had nevertheless propagated as their ancestral soil for a life in freedom and self-determination. These nations only experienced freedom, rule of law and growing prosperity again when they entered the post-national development of the European Union.

4. I also grew up in the Second Republic of Austria with the historical verdict that the old Austria, the Habsburg monarchy, was a “dungeon of nations”. The fact that I did not question this term for a long time is astonishing. For I did notice, or at least I felt, how much Austria mourned its lost greatness, how fierce was the phantom pain of Vienna, this magnificent metropolis that was now disproportionately large for such a now small state, and which was derided as an urban ulceration. Of course, I felt the melancholy, not only from my grandparents, but it was also in the air, and showed itself in people’s pride of the façades of Vienna’s inner city, pride in imperial settings, as if their glorious grandeur showed the real identity of the small republic. Even when Austria decided to establish a House of the History of the Republic, no new bold, modern building was planned that could express the Republic’s fortune, no, this House of History was squeezed into the staircase of the Habsburg Hofburg Palace, as a museum of the Republic within the living walls of the monarchy.

This pride in the imperial heritage, the mindless marketing of the spirit of old Vienna, and at the same time longing for lost greatness, all this does not seem to fit together with the condemnation of the empire as a “dungeon of nations”. And yet there is an inner logic underlying Central European nostalgia: namely, the completely grotesque splitting of cultural and intellectual history from political history. Central Europe is a term that essentially denotes a cultural area, with Vienna as the fixed point, radiating far into the East, as far as Galicia. And the Habsburg Monarchy denotes a political entity that is said to have been a “dungeon of nations”. “Dungeon of nations” was a term used by the nationalists, and it is astonishing that Austrians, who mourn the monarchy and sell its heritage as a tourist attraction, have adopted the verdict of the nationalists who destroyed the monarchy. It is clear today, or should be clear, as a lesson of history: a supranational entity does not fail because a common state of law, common market, common currency, and common administration cannot work for different “nations”, because the interests and cultures of the different nations are too different. The fact that supranational statehood can work was proven by the cultural and intellectual wealth produced by historical Central Europe, and it is proven today by the European Union. Supranational or post-national statehood fails only because of one problem: nationalists – whose ideology has regularly led to divisions of societies, to images of the enemy, to conflicts due to competition between nations and ultimately to the greatest crimes against humanity. It’s that simple, and that stupid. A delusion. The European Union may soon prove this again, when I think of the growing nationalism in certain EU member states, and the populism of certain politicians and especially Central European heads of state who call the EU the EU-SSR and Brussels the centre of the renewed subjugation and colonisation of the (Eastern) European nations.

And there is something else that amazes me today when I think about how naturally and unquestioningly I associated the term “dungeon of nations” with the Habsburg monarchy as a student and young adult. That’s how I learned it, that’s how it was always said – even though we had a veritable dungeon of nations on our doorstep that deserved this designation: the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and their Glacis States! This was not a union of free republics, not a common cultural space in which freedom of thought and research, exchange and cross-fertilisation led to a lasting unleashing of art, culture, and science. The Hungarian uprising of 1956, the Prague Spring of 1968 were brutally crushed by Stalinist tanks, the populations of the states behind the Iron Curtain were literally incarcerated. But I have never heard the term “Volkskerker” (dungeon of nations) in this context. “Volkskerker” was a term exclusively used for the Habsburg monarchy – over which a canopy of melancholy and nostalgia was stretched at the same time, with the pathetic grins of business-minded heirs patronisingly pitying the poor people of Central Europe behind the Iron Curtain.

5. Can it be that I am idealising the achievements of Habsburg rule in Central Europe? At least as far as the framework conditions that were based on communal law and common administration, and not on creating a sense of community through national identity? Is this idea not all too abstract when measured against the real living conditions of the people, the social misery, poverty, hunger, and illiteracy that had determined life in large parts of the crown lands in the East? Didn’t this misery lead people, instead of rejoicing over “cultural wealth”, to not only adhere to nationalist slogans, but to also try with all their means to emigrate and seek their fortune and a better life in the New World, in America?

I think it is crazy and historically negligent to accuse old Austria of not being a developed welfare state, at a time when none existed anywhere else. And we can only conjecture about whether the largest and best organised labour movement in the world, the Austrian one, would have enforced welfare state standards step by step if the old Austria had not been destroyed by the nationalists, who promised social justice and social advancement even to the smallest power mongers as long they belonged to their own ethnic group, with the well-known results. But one thing is historically attested to and very interesting in this context: there were indeed massive waves of emigration from Europe to America between 1885 and 1910. The largest number of “economic refugees”, of emigrants, did not come from Central Europe, however, but from the Western nations, most of them from Germany, then from Ireland, Scotland, England, Sweden and Italy. Only just under 7% of all European emigrants came from the Austrian crown lands.

Something else is interesting in this context, and here we hear derisive laughter in the long corridors of history: the most important port of call for emigrants from Central Europe was Auschwitz. Here were the offices of Hapag (Hamburg) and Lloyd (Bremen), which propagated and organised the journey to America in this area and sold steerage tickets. Auschwitz was then the Central European portal for the wretched for a hoped-for future in the New World. Those who said Auschwitz at that time thought of a better life, thought of America.

No, I am not idealising anything. I never dreamed of becoming a Habsburg nostalgic, nor am I one, even though I wonder now, as I write, that I might give that impression. I grew up in the Republic, never suffered from the loss of Habsburg greatness, but rather from the continuities in the history of the Austrofascist mentality, which constantly revives itself, and the Nazi mentality, which is only slowly dying off and is still perceptible in Austrian everyday life. But precisely as a republican, today I see the historical reason for the idea of a united Europe, as it is painstakingly developing in the European Union, once again in the fight against nationalism. And I see the historical roots of the EU in Austria-Hungary’s claim at the time to develop statehood without the pretension of nation-building, even if West Europeans cannot understand this.

Jacques Delors’ phrase “If I could start again, I would start with culture” is indeed an invention; while there is no proof that Delors ever said this much-cited phrase, its invention was only possible and could only gain credibility because it was indeed culture, through which the reason for and productivity of the peaceful coexistence of “nations” in a common state of law was sustainably demonstrated in Central and Eastern Europe before 1914. And this is also the reason why we always associate “Central Europe” with a “cultural area”, as if it did not need a political framework.

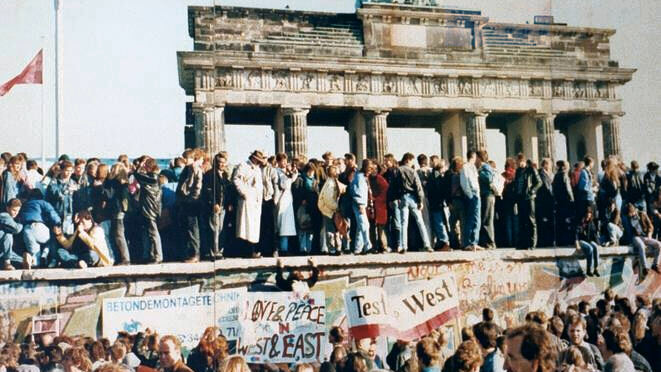

6. At the same time, “Central Europe” is a term that was misconstrued as a utopia during the Cold War, as if the nostalgically sepia-toned intellectual history of Central Europe were a political promise of the future for the countries behind the Iron Curtain under Soviet Russia. Basically, the reference to Central European cultural and intellectual history was used to prove that Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Poland and the Baltic states actually belonged to the Western cultural sphere and that they would return to it as soon as the Soviet Union lost the systemic struggle with the West. But since no one seriously believed in the end of the Soviet Union (one can say: until twenty-four hours before the fall of the Berlin Wall), the alleged utopia was nothing more than a footnote in Cold War propaganda, intended to prove how illegitimate Soviet rule in the Central and Eastern European states was, also for reasons of cultural history.

The West’s pragmatic policies were naturally not oriented in any way to this history and its ostensible perspective, but pursued a policy of rapprochement and Cold War peace through trade, or more precisely, through the verbalisation of Western values called Realpolitik: free trade, equality on the world market and in international institutions, fraternity in pricing. Political pragmatism simply meant situationism, without developing a perspective for what the West had hoped but no longer believed would actually happen.

And this also explains Milan Kundera’s outburst of rage, who in his 1984 essay “Un Occident kidnappé” accused the West of having sold out the countries of Central Europe. What was façon de parler for the politicians of the West, Milan Kundera presented at the time as existential: yes, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe naturally belonged to the Western cultural sphere of Europe, and to Russify them was kidnapping, was rape. But this statement should not be addressed with fine-minded reminiscence, but should clearly state that as far as the division of the world at the time by the superpowers, the political map of Europe should never have been accepted. The map of Europe was interpreted differently by East and West; it was Milan Kundera’s aim to change it. He wanted a clear demarcation of European culture and civilisation from Russia, which he saw as a danger and threat, not only through Stalinism, but fundamentally through Orthodoxy and the tradition of Asian despotism. Can one (or without asking: one can) call Kundera’s vision of Europe from 1983 prophetic, fulfilled by the accession of the Central and Eastern European states to the EU in 2004. And one can (or without asking: one must) also call his warning about Russia prophetic, an anticipation of Huntington’s Clash of Civilizations, which emerged in shocking radicalness in 2022 in Russia’s war against Ukraine.

The only interesting thing from today’s perspective is that Milan Kundera did not count Ukraine as part of Europe at all, but rather ascribed it to Russia, despite Galicia and Bukovina, cities like Lemberg or Czernowitz, which we almost remember as a paradigm of Central European culture, with or without Habsburg nostalgia. I wonder if this had anything to do with the fact that Kundera knew that Khrushchev and Brezhnev were Ukrainian…?

Just when Kundera was writing his Central European essay, then Austrian Vice-Chancellor Erhard Busek reminded us that Ruthenian/Ukrainian was also spoken in the Austrian parliament until 1914.

In any case: the EU’s so-called eastward expansion initially proved Kundera right. A number of Central European states were freed from Russian despotism and returned to Western Europe – which, however, can now no longer be so clearly described as a cultural area, but had essentially become merely a common market. This is now the only thing these states have in common, after they had previously known only this other commonality, with no memory going further back: that is, being subject to the despotism of the Russian orbit.

7. The common market alone is not a restoration and certainly not a further development of what Central and Eastern Europe historically defined as a common space. For what we call the culture of Central Europe was actually not this at all: ethnic groups’ pride in a nation that lives out its freedom in sovereign arbitrariness on a national territory. The regular breach of European Community law by states like Poland or Hungary shows how little their return to Europe has to do with a return to Central Europe. One could accuse them of forgetting history, because all their misery, from which they now see themselves liberated, was the consequence of their nationalist furore at the beginning of the terrible 20th century. And we see their nationalism now more than ever. However, it is not exactly forgetting history, but referring to a completely different history, which I must call the blind mirror of the First World War, which is the sin of the 20th century in terms of international law. Namely, Woodrow Wilson’s doctrine of the “right of peoples to self-determination”, which found its way into international law and became a basic axiom of the United Nations Charter. This doctrine assumes (and cannot be thought of in any other way) that there are ethnic groups that have a claim to a certain clearly defined territory. This is of course crazy, completely narrow-minded, and simply inhuman if we think, to stay on the topic, of historical Central Europe, where out of very realistic insight, the statute of personal autonomy instead of territorial autonomy had already been introduced. But anyone who thinks of territory and ethnicity together is, nolens volens, in favour of the ethnic cleansing of a certain territory, resettlement, exaggeration of one’s own idea of oneself and fomenting conflicts against others, against internal and external enemies, not to mention terror against minorities, but also against critics of national myths (as well as mythical exaggerations of a “core country”, a territory outside the current national territory) and of national representatives… This is the reason why Lenin, Trotsky and Stalin could so easily agree to this doctrine. And this is the justification today that equality and freedom and the claim to peace and dignity of human beings do not apply when “national interests” stand against them.

“National interests are always the interests of national elites”, said Jaques Delors allegedly. I don’t know if the quote is correct, maybe it is just as invented as the quote about culture. It is true in any case. Freedom is not guaranteed by international law, which is not about justice, let alone reason, but is dependent on the power of interests. The Kurds, just for example, are not a people? Do they not live on a clearly definable territory? Why does the right of self-determination of peoples not apply to them? Of course we know why. Just like with the Basques, or the Corsicans. Nationalism is still the basis of international law, although at least in Europe we were promised that nationalism would be vanquished with the EU. Instead, with the liberation of Central Europe the old destructive nationalism was revived, spoon-fed and nurtured. No one in their right mind can really understand why, for example, Yugoslavia had to be broken up into small nation-states under Western European shouts of ‘come on’, only to have these new nation-states incorporated one after the other into the post-national project of the EU, just as it is difficult to logically comprehend why the Czechs and Slovaks urgently needed to establish their own nation-states before they entered the EU.

I think international law is a farce. If only because it is called international law. Human law is enough. Human law must suffice.

8. Russia, which has long since ceased to be the Soviet Union, is today showing the face that Milan Kundera described as fundamentally Russian 40 years ago in Soviet times. Today, of course, it must be clear what did not need to be emphasised at the time in the front line between West and East: that a “people” should not be held hostage to criticism of the system. So: yes, of course, not all Russians are like that. We differentiate. We love Russian cultural achievements, we admire the courageous people who criticise and resist the Putin regime, but this is not about talking about Russians in a differentiated way, but about Europe’s demarcation from Russian imperialism, from the Tsarist Empire to the Soviet Union to Putin’s Russia.

Central Europe was liberated from Russian rule. Russian glacis states became members of the EU and NATO. But the eastern enlargement of the EU was not the incorporation of Central Europe and its culture, its historical experience with transnationality and personal autonomy, not a correction of a departure from history, but only the liberated cheerleading of nationalism, the destruction of the claim that European history – and yes: European culture! – is no longer reduced to a combination of national histories. The so-called eastward enlargement was in reality a westward enlargement in the east.

Central Europe was kidnapped a second time after the end of the Soviet Union: by the cultureless princes of neoliberalism and the high priests of the pure transcendence of market faith, represented by the zombies of nationalism. And they, like all of us, are stunned and uncomprehending in the face of the brutal aggression of Russia, which wants to conquer territory in Ukraine that it calls its “heartland”.

It is a crime, it is heinous – but it is, in the “clash of civilisations”, the common intersection of European history (with its nationalist wars and literally crazy border demarcations and regular pragmatic recognition of the political consequences of arbitrariness and violence) and Russian claims to correct history. We are witnessing the bewilderment of small nationalists in the face of the aggression of a big nationalist. And what I fear is that the heroism of Ukrainians defending their country will also only increase their nationalism immeasurably. It will be the definitive nationalist lid on the once polyglot, multi-ethnic, supranational melting pot of Galicia.

9. In his essay, Milan Kundera emphasises the special significance of the Jewish spirit for the development of the Central European cultural area: “…grown up in a spirit that was more or less above national disputes, the Jews in the 20th century were the essential cosmopolitan and integrative element of Central Europe, his intellectual glue, the condensation of his esprit, the creators of his spiritual unity.”

Of course, this is a reminder that despite all the historical melancholy about the fate of Central Europe and all objective reflection about the historical development of this region, one thing must be clear: after the Holocaust, Europe can never become what it was intended to be.

In the play “Third of November 1918” by Franz Theodor Czokor there is a touching scene that condenses the fate of Europe: the war is over, the colonel of a unit of the k. u.k. Army refusing to recognise the new borders, and commits suicide. His people pay him their last respects. The officers and soldiers approach the open grave and each one throws a small shovelful of earth onto the coffin, with the words: earth from Hungary, the next: earth from Poland, the next: Slovenian earth, and so on, earth from Carinthia, Czech earth, Italian earth, until finally the Jewish regimental doctor steps up to the grave and says: earth from Austria.

That was the burial of Central Europe.

What does it mean, that in 1955, after the signing of the state treaty that gave little Austria its sovereignty, the rebuilt Burgtheater in Vienna initially planned to show this play by Franz Theodor Csokor as a celebration of New Austria, but then decided against it and instead staged Grillparzer’s “King Ottokar” as a major national theatre?

Meanwhile, a demographic miracle was happening in the Central European cities: Despite the mass extermination of Jews, the cities had almost exactly the same population as before. Who took the place of the exterminated or expelled Jews? In the literature this is called “immigration”. It was mainly farmers who now had the prospect of making their fortune in the city. It was the time when cows were kept in backyards and goats on balconies. That was the new symbiosis between the rural population and the city. One should not make fun of it and certainly not show contempt. It’s just a symptom of real history. And you can understand why the grandchildren and great-grandchildren, who are now doctors, lawyers, managers and TV news editors, are grateful for a system that looks at “their own people”.

10. The automobile industry in Bohemia, the oil industry in Eastern Galicia – it is not true that the regions of Central Europe were backwards. But if something historically sunken has become irrelevant today, it is this. It is included in the EU’s infrastructure promotion and locational policy – even if I find the economic term “business location” less attractive than the wistful term “living environment”. But what hurts is that in a united and, if possible, really unifying Europe, the multi-ethnicity of Central Europe and its culture is no longer even good enough for nostalgia.

I am Central European. I am Jewish, homeless in my homeland.

11. “Let’s not forget that the only way we can oppose today’s history is to oppose history in the first place.”

Witold Gombrowicz.

“I would like to engrave this sentence by Witold Gombrowicz over the entrance to Central Europe.”

Milan Kundera.

* In German I use the term “Mitteleuropa” for “Central Europe” because it describes a historically grown, and at the same time nostalgically charged, cultural area, as Milan Kundera reflected on in his essay “Un Occident kidnappé” or “Die Tragödie Zentraleuropas” (“The Tragedy of Central Europe”), and not the term “Zentraleuropa” (also translated as “Central Europe” in English), which describes the research field of historians who mean to deal with the political history of Poland, Czechoslovakia and Hungary in particular. Kundera wrote his essay in French, which does not have the term Central Europe in the sense mentioned. I am sure that if Kundera had written the essay in Czech, he would have used the term „Mitteleuropa“ – which is why I think the German translation of the title of Kundera’s essay is wrong. I am aware that the term „Mitteleuropa“ had a very specific use between 1938 and 1945, to denote the economic colonization and military subjugation of Eastern Europe. But „Mitteleuropa“ is not used in this sense today, either in everyday language or in science.

© Rafaela Pröll/SV